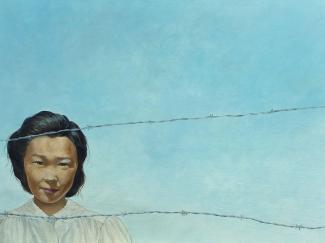

Gaman · Endurance

Mass Uprooting

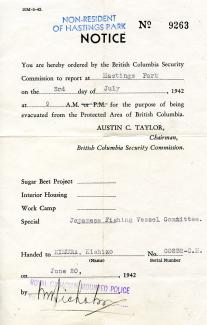

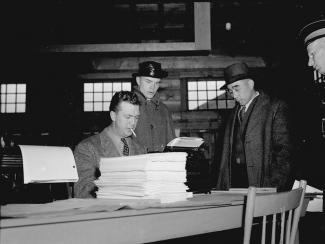

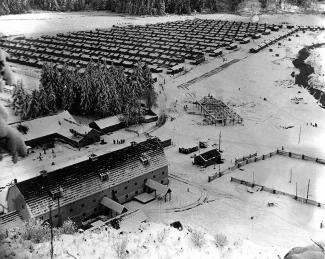

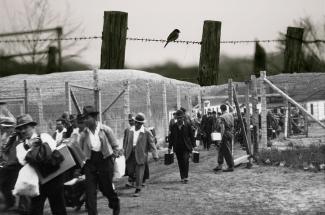

During the Second World War, all persons of Japanese ancestry living on the coast, are uprooted from their homes and communities. Regardless of citizenship, they are stripped of all properties and possessions.

In early 1943 the government breaks its promise. They enable the Custodian of Enemy Alien Property to sell Japanese Canadian property without the owners' consent. Between 1943 and 1947, the government forces the sale of all their property in coastal British Columbia. For those living in government-run internment camps, the Custodian holds the proceeds from the sales. They limit Japanese Canadians' access to these funds, paying out meagre allowances. These allowances must cover the expenses of their life in internment camps. Japanese Canadians are not silent in the face of this injustice. They write thousands of letters of protest. Government officials take particular notice of almost three hundred (292), written by 247 different authors. They collect these in a file and store them in Vancouver. Many other letters are spread across the massive records of the Custodian of Enemy Property.

News of this forced sale is met first with disbelief and then with outrage at the loss of everything they have built.

Transcript

[A Japanese woodblock print shows two sailboats floating near small islands surrounded by turbulent rapids. The image morphs into the real-life vista of the same scene.]

February 24th, 1945.

[A young woman reads :]

You have informed me that my property and chattels have been sold.

I never consented to the sale, but have at all times and do now object to the sale of my said property.

[The woman sits in a shipyard building.]

However, I am in destitute circumstances, for my present earning is not sufficient to support my family, owing to the weather not being suitable to logging operations here.

[She stands in an old machine shop.]

I would request you to forward me fifty dollars from my fund each month, in order to maintain myself and my family.

[A waterfall appears.]

I wish it made clear, that it is only being accepted under protest, arising out of what I consider the wrongful sale and dispossession of my property. Need of the fund is very urgent, it would be appreciated if you will kindly forward it immediately.

[Sitting on the shipyard's boat ramp, the young woman speaks :]

My name is Laura Fukumoto, and that letter was written by my great-grandfather, Toyemon Fukumoto.

[She smiles, then looks out on the water gently lapping at the wooden ramp.]

Transcript

[Atmospheric piano music]

[A Japanese woodblock print shows a coastal settlement with forested mountains in the background. Japanese villagers holding parasols cross a wooden footbridge. The scene morphs into the same modern-day coastline, where all that is left are decaying wooden pilings in the shallow water.]

>> A man’s voice:

Dear Sir: In your letter, you stated that you cannot give consideration to my request to dispose of my own property to whom I like.

[A man stands in an old abandoned shipyard building, gazing out the window.]

>> The seated man reads from a sheet:

You stated that it is now impossible for you to give consideration to a sale to Mr. Bruce McCurrach, because the sale of my property, together with other rural properties, was made to The Directory, the Veterans’ Land Act.

>> The man speaks:

I understand from your letter of August 30th, 1943 - that this transaction took place on January 1st, 1943 - exactly one year and four months ago.

>> The man speaks:

But to this day, you have not given me the sale price of my property - which you sold without my consent.

[With the sun softly shining through grimy windows, Brent stands in a workshop. Moving slowly over the surface of the coastal water, fragments of the old pilings pass by, reaching up like the twigs of a submerged tree from the surface of the smooth water. High clouds fill the blue sky above the mountains.]

Even those properties sold under expropriation law, the property owner has the right to appeal for fair sale price. You advised me that you sold my property, and yet you do not know the sale price.

[The man slides open a door leading to a pier outside.]

I was under the impression that your office is there to look after the interests of the Japanese people. At least that is what you told me at the time of registering my property. I shall hold you responsible.

>> The man looks up as his voice over continues:

Yours truly, Tokuji Hirose.

>> The man speaks:

My name is Brent Hirose. This letter was written by my great-grandfather, Tokuji Hirose, in Winnipeg, Manitoba - where my family still live today.

[Wearing a dark shirt, Brent stands in the shipyard building, with sun filtering through the cracks of the wooden planks in the wall behind him.]

The unauthorized sale of their possessions causes immeasurable despair – years of hard work wiped out with the stroke of a pen.

Transcript

[Atmospheric piano music]

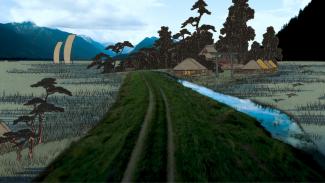

[A land bridge stretching through a flat, grass-covered plain at the base of several mountains appears. Two parallel ruts create a roadway along it. The surrounding marshland is at first depicted in a Japanese woodblock print. Then, the current, photo-realistic image of the same scene replaces the scenery, with water on either side of the grass-covered, well-worn pathway through the marshlands. The aerial view of the scene rushes by.]

>> A man’s voice:

Dear Sir: The Director of the Office of the Custodian in Vancouver has notified us of your policy of liquidation of Japanese property.

>> A man speaks:

Because of this policy, my property has now been catalogued for sale.

[The man reading the letter, now wearing gumboots, strolls along a gravel pathway lined by trees. Overhead trees cast shadows on the ground.]

This liquidation is against your promise, and my wishes, furthermore it is utterly undeserved.

>> The man speaks:

My husband invested heavily in our home and garden. Both of us are proud of our collection, not only for its value but also for its endearingly beautiful response to our care and for the deep satisfactions it gave us.

[The man crosses an arched footbridge over a pond, leading to a Japanese garden. Green grass forms a carpet for several varieties of exotic plants, including Japanese maple. Smooth rocks lie placed among low-lying shrubs.]

Our unique collection was well known and was widely appreciated by fellow hobbyists.

>> The man speaks:

Testimony of this appreciation is shown in the way people would stop to compliment us as they strolled by, many requested permission to walk through our garden.

[More of the garden’s varied flora is shown.]

>> The man speaks:

During a survey conducted by the Victoria Horticultural Society to choose “Gardens that beautify our streets”, Mr. Takahashi was granted the Award of Merit, dated August 16, 1935.

[The walking path extends into the garden’s pond, where the man stands, with the arched footbridge visible across the water.]

Two years later during the Royal Visit, their Majesties the King and Queen drove past our home. We treasure the memory of seeing Her Majesty turn her head to see our garden.

>> The man speaks:

When the evacuation became a stark reality, my husband received many offers from nurseries to buy our collection, but he declined.

[The man stands on large, flat stones crossing a small stream.]

Didn’t you promise to keep intact all properties until we returned?

>> The man speaks:

Isn’t the garden an asset to Victoria, just as much as it is a pride and joy to us?

[A bird’s eye view shows the entire garden from above, with the footbridge crossing over the pond in the foreground. Next, the man sits near one end of the bridge, gazing at a twisted, moss-covered pine tree branch.]

My husband is now too advanced in years to earn a livelihood, his health is beginning to fail, and is looking forward to retirement next year. After all our efforts in good citizenship, we do not deserve to have our retirement jeopardized by the liquidation of our properties. Yours very truly, Toyo Takahashi, File Number: 9363. My name is Dr. Bruce Yoneda.

>> Bruce speaks:

This letter was written by my grandmother, Toyo Takahashi, whom I remember well. As a youngster growing up in Edmonton, we made several memorable trips from Edmonton to Toronto to visit my grandparents.

[Bruce sits in an old wooden building with sun filtering through the wall's wooden planks behind him. His gaze drops to the letter in his hands.]

Some Japanese Canadians answer the meagre amount the government is offering for their property with a flat refusal.

Transcript

[Atmospheric piano music]

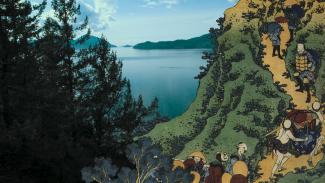

[A Japanese woodblock print shows a line of Japanese men and women ascending a coastal mountain trail, loaded down with goods and packages. An image of the same, but modern-day view then takes its place. The forest recedes, revealing the ocean beyond with the mountains reflected in the smooth surface of the water.]

>> A woman’s voice:

Dear Sirs:

>> She speaks:

I am in receipt of letter and cheque amounting to 48 dollars and 54 cents, for dishes and kitchenware at Tairiku Nippon-Sha, which you say was sold at auction.

[A trail winds through a rainforest.]

I had treasured these articles and had not wanted or asked them to be sold.

[A forest surrounds a stream flowing over smooth rocks.]

That is the reason why I had asked Mr. Albert H. Young, the barrister, to see if he can do anything in the line of having my property sent to me.

There were 6 boxes in which there were 25 sets of Japanese china, value at $7.00 per set; articles which were new, and not unpacked from its packing straws; and many others which you cannot buy again.

[A small waterfall flows into a pool below.]

>> The woman speaks:

Did you sell these individually, or by the crated box? There is no price as 48 dollars and 54 cents for them.

[The forest trail appears once again.]

I am in need of the cash right now, so I am taking it, but I am not satisfied with both the idea of having my property disposed without notifying me, and the amount you have sent me for them. So, am putting in a claim to the Co-Operative Commission when they make representation to the Government.

[A cascading waterfall appears in the forest. The woman looks up.]

Yours truly, Katsuyoshi Morita.

My name is Emiko Morita. My grandfather wrote this letter, Katsuyoshi Morita.

[Emiko sits in an old wooden building, the sun filtering through gaps in the horizontal wall planks.]

Transcript

[Atmospheric piano music]

[A Japanese woodblock print shows a serpentine tidal channel surrounded by trees and rotting stumps in a saltwater marsh. Forested mountains stand in the background. The scene morphs into the same, photo-realistic view, with misty clouds hovering over the scene.]

>> A young woman’s voice:

Sir: I am in receipt of the articles sold by your office of my fixtures, personal belonging and merchandise, etc., from Store and residence in Port Essington.

[The dark-haired woman stands, looking out the window in a rustic kitchen.]

Your list is by no means complete; many items are missing.

For example, from Port Essington Store and residence:

[Viewed from above, a dense forest of evergreens.]

2 hand trucks

1 typewriter

2 cash registers

5 tons of coal

10 cords of wood

3 field glasses (locked in safe)

[The woman sits in a small bedroom, looking out the window adorned by wispy curtains.

6 Japanese costume wigs

4 silk Kimonos

>> The woman speaks:

4 male Kimonos

1 frock and several accessories

[An aerial view of the grassy marshland, where fragments of wood, tree trunks and stumps litter the landscape.]

>> The woman speaks:

Dishes, etc., all new, all articles sold for ridiculous amounts.

For example: $425.00 Daylon scale for $50.00.

[The woman sits at a desk, moving wooden squares.]

From my Vancouver House, 1864 W. 8th:

Missing:

1 wooden bed

1 single mattress

1 double mattress

>> The woman speaks:

From House at

North Pacific Cannery:

1 double mattress

[The woman sits at a vintage sewing table. She reaches for the sewing machine’s wheel.]

1 comforter

1 Coleman lamp

1 ice-cream freezer

1 bath tub

4 chairs

1 hand truck.

Above is not a complete list of missing articles.

Yours truly, Shimo Kameda, File #1582

[The young woman, her brown hair held up with a traditional comb, looks up from the letter.]

My name is Carmel Tanaka, and this letter was written by my great-grandmother, Shimo Kameda.

[Carmel looks down at her sheet.]

Japanese Canadians’ protests are defeated by the government's machinations. In 1943, they start a legal challenge to the government's seizure and forced sale of their property. But it is stalled and ultimately unsuccessful.

Transcript

[Atmospheric piano music]

[A mountain stream looms - the bottom portion of the image is real, while mountains appearing in the top half are represented by a Japanese woodblock print of the same scene. The photo-realistic image then replaces that image, with low clouds shrouding the base of snow-capped mountains. Now inside, a woman sits at a desk in a study, pen in hand.]

>> A woman’s voice:

Dear Sirs: Have written to the lawyer about the selling of my house.

Have heard from the friends in Vancouver, that those prices of the houses are way over the price I mentioned in my last letter.

>> The woman speaks:

So if you could please put the sale price for $1700.00.

[The woman appears at the threshold of a small home, her body appearing in silhouette as bright sunlight floods in around her. Entering a study, she gazes out a window. Outside, a mighty river thunders through the forest. Back in the study, the woman sits at a desk with an antique typewriter, a pencil poised in her right hand over a pad of paper.]

And please let me know the result.

Thanking you, yours truly, E. Nakashima. P.S. As for the statement for the rent, have not received any for the last few months, so please send it at your earliest convenience. Thank you.

My name is Kirsten Emiko McAllister. I’m the great-grand-daughter of Eikichi Nakashima.

>> Kirsten speaks:

My great-grandfather also was part of a lawsuit against the Canadian government in 1943. He and three other Japanese Canadians questioned the right of Canadian government to sell the property of Japanese Canadians.

[Kirsten bows her head.]

The government responds to the flood of letters with dispassionate bureaucratic language. In 1947, the government sets up the Bird Commission to give the appearance of responding to Japanese Canadian lost property claims. Most claimants receive only a fraction of what they have lost. This is just one impossible battle that the Japanese Canadians continue to fight even after the war is over.

Dear sir,

Your letter has been placed upon our files so that your comments in regard to this sale will remain on record, but we can only advise you that we are unable to consider any alternative to this matter. Your remarks have been carefully read and we can appreciate the disposal of your property will be a matter of personal concern. However, the sale of properties to the Director, The Veterans’ Land Act was carried out as part of a policy of liquidation outlined by Ottawa on the basis of appraised values.

– Yours truly

W. E. Anderson,

Farm Department

Protest Letters

Click for access to digitized letter library

Final Betrayal

As the war comes to a close, the sale of confiscated properties continues. The displaced Japanese Canadians are given two choices: move east of the Rockies, or be exiled to Japan. They lose not only their property, but also their right to return home.