Ikigai · Worth

Working Together

Japanese migrants bring skills, a strong work ethic, and belief in working together.

The Issei work hard to achieve their dreams for home and a better life. They find work in resource industries up and down the British Columbia coast. Some begin to farm. The first Issei are men, but they soon send for the wives they’d left behind or arrange for “picture brides” to join them.

Women not only work alongside their husbands, they also transform rowdy otoko machi – villages of men – into stable communities. To meet the needs of these settlements, Japanese Canadians open grocery and dry goods stores, rooming houses, barbershops, photography studios, brothels, tofu-ya (tofu shops), tailor shops, confectioneries, restaurants, newspapers, ofuro (bathhouses), and other businesses. Working together, they build a solid foundation for families and a new home.

Transcript

[Atmospheric piano music]

[An image split in half: On the left, a black and white photo shows a Japanese man standing with a woman, who holds a baby in her arms. At her feet stand a young boy and girl. On the right, an image of an old barn bathed in sunlight. Superimposed over the image of the family, is a cut-out of a young Japanese boy, taken from different black and white photo.]

>> A man’s voice:

My father immigrated from Japan in 1905. He worked in the sawmills, and he advanced through the sawmills to reach a position of superintendent.

[An archival photograph of a sawmill along a warf appears, followed by the full photograph of the family of five shown earlier. This is followed by more archival photographs of the growing family.]

That enabled him to save enough money to buy 5 acres of farmland in Mission City, BC.

>> The man speaks:

Now, this was raw land, so, in order to make it arable, they had to cut all the trees down, and - what they used to do was use dynamite to blast the stumps out of the ground. So, it was just back-breaking work and time-consuming, and it essentially took years and years for them to finally be able to clear the land.

By 1941, they were reaching a point where all their back-breaking work would bear some fruit and, it was basically strawberries in that area.

[The man stands in a farm field of low-lying plants, with two young women and another man crouched on his haunches. Fourteen Japanese workers pose crouched over a row of strawberries, wearing broad-rimmed hats.]

And, in 1942, my father looking forward to a bumper crop.

[The man sits in an old wooden building, the sun filtering through gaps in the horizontal wall planks.]

[Onscreen text: Archival Photographs courtesy of Tosh Kitagawa Family Archive

UBC Open Collections JCPC_20_003

NNM 1994.83.7 Strawberry Patch]

Building Community

Japanese Canadians build communities around shared language, culture, and values.

Japanese Canadians build communities in Canada through various institutions. Their values are reflected through their homes, farms and gardens, schools, and churches. They raise families, adopt Canadian customs, and bury their dead in Canadian soil. The second generation of Japanese Canadians, the Nisei, are born in Canada beginning in 1889. Though Canada is their home, the Issei teach their children traditional Japanese values. These include gaman – to endure; giri – to be dutiful; and ganbare – to persevere. These values will play a lasting and significant role in the lives of the Nisei in Canada. Their Canadian education, in public schools and universities, is important as well. The Nisei learn to believe in Canada as a country where all citizens are treated equally under the law. They trust British concepts of equality, fair play, and the rights of the individual.

Transcript

[Atmospheric piano music]

[A split-image: a little girl sits with her infant brother in a black and white photograph, next to an archival image of boats docked at a pier. Next, the little girl is now highlighted, superimposed over the full image of the boats.]

>> A woman’s voice:

My family’s been living in Canada for 122 years.

>> The woman appears:

My paternal grandfather was the first to arrive, he came in 1895. He went back for a bride, and then started his family. All his children were born in Canada.

[An archival photograph of some of the family members appears.]

And there was a sense of belonging to the community, because they shared the share culture, the language, the values.

[In another archival photograph, three men, two women and three children stand outside a fish market.]

When the children arrived, especially the nisei and sansei generation, like my generation, we were living in two worlds.

[A large gathering of children poses in traditional Japanese clothing outside the Japanese Hall, along with some adults. A solemn young man poses in an archival photograph, wearing a kimono with a black belt around his waist, then a young woman poses next to a sofa, wearing a North American-style jacket and hat.]

At home, we were living in the world of my parents and grandparents, whereas in school we acquired the values of being Canadian.

[A photograph appears: elementary-aged Japanese school children with their Caucasian teacher.]

And so, I could say that we were comfortable in both worlds.

[In another split-image, a young boy plays a harmonica with two young men, one of whom holds a violin in a photograph to the left. To the right, three young men wear body armor and hold trophies.]

>> The woman speaks:

At home, for instance, my grandparents had Japanese records and so we would listen to Japanese songs. And they would follow the Sumo tournament.

[In an archival photograph, three slim young men wearing black loincloths pose in front of several men wearing suits. Three young women participate in a ceremony, holding flowers while surrounded by young girls with bows tied in their hair.]

Whereas, at school, we learned songs like “There Will Always Be an England”, “Maple Leaf Forever”, “God Save the King”, and that was part of our culture, too.

[In another photograph, several girls wear traditional Japanese garb at a gathering, while one holds a Union Jack flag.]

>> The woman speaks:

Somehow, we managed to survive in those two worlds, and actually thrive because being bi-cultural had a lot of advantages.

[The woman sits in an old building with wood slats.]

[Onscreen text: Archival Photographs: Courtesy Masako Fukawa Family Archive

CVA 260-106 Steveston Fishing Village

NNM 2010.59.1 Maikawa Fish Market

NNM 2010.80.2.130 Girls in Kimonos, Japanese Language School

NNM 2010.80.2.107 Strathcona Elementary 1941

NNM 2010.2.4.355 Mr. Amemori, Mr. Tashiro and Mr. Moriyama, Mission B.C.

NNM 2010.35.2.2.009 Kendo

Sumo Photo Courtesy of Aki Horii Family Archive

NNM 2010.23.2.4.214 Celebration of the Royal Visit]

Fighting to Belong

In the face of racism and exclusion, Japanese Canadians work to belong to the country.

Both Issei and Nisei Japanese Canadians face a world where discrimination is a daily reality. Anti-Asian sentiment is widespread on the west coast. Canadians of Japanese, Chinese, and South Asian origin are resented for doing the same work as white workers for less pay. Most professions are closed to them, and even those born in Canada are barred from the right to vote. Home is often a hostile place outside of their immediate, tight-knit communities.

Despite the discrimination they face, Japanese Canadians are eager to prove their loyalty to Canada. They raise money for local hospitals, and participate in celebrations for the British royal family. During the First World War, hundreds of Issei volunteer to serve in the Canadian army. But the struggle to be recognized in their homeland continues.

Transcript

[Atmospheric piano music]

[In a black and white split-image: two little boys in a photograph on the left, soldiers in trenches with machine guns on the right. Then, the older of the two boys on the left is highlighted.]

>> A man’s voice:

Northeast corner of Jackson and Powell, there was a small confectionary store run by the Matsumoto couple.

[The two-storey store appears, in an archival black and white photograph, on the corner of a street in East Vancouver.]

And he, my grandfather, would take me in there and would buy me a Japanese bun with bean curds.

[A photo of the man as a young boy with his grandfather appears.]

>> The man speaks:

When I started practicing medicine in 1961, the Matsumotos became my early patients. And only then did I find out that he served in the First World War.

[An archival photo appears of a man posing in his army uniform, worn under a full-length leather jacket.]

>> The man speaks:

And he, by this time, he had lung damage from inhaling the poison gas.

[The man, once again, posing in a photo, wearing a military uniform. Next, soldiers sit in a trench at with a machine gun in a black and white archival photograph.]

Even to enlist in the Canadian Army in 1914…British Columbia being so racist… they would not accept Japanese immigrants as enlisting.

[Another photo of the man appears, wearing a military officer’s uniform while sitting in a chair. Then another photo appears, with Matsumoto posing with other stern-faced army officers.]

>> The man speaks:

So, they travelled by train and by bus to Calgary and Lethbridge, Alberta - where they were accepted into the army. And about 222 isseis enlisted and of those men 54 people were killed in action. And that’s why issei community set up a monument in Stanley Park.

[The tower-shaped monument appears in a black and white photograph, along with Japanese men holding wreaths at a memorial ceremony as well as a young boy standing at the base of the monument, wearing a kilt.]

>> The man speaks:

A war memorial monument just west of the aquarium – to honour these men, who fought for Canada.

[Aki sits in an old building with wood slats.]

[Onscreen text: Archival Photographs : Courtesy Aki Horii Family Archive. JCCC 2001-11-87 Star Dairy

NNM 2010.23.2.4.557 Kingo Matsumoto

NMM 2010.23.2.4.558 Kingo Matsumoto

BAC Mikan 3241489 Vimy Ridge

W1-7 Sgt Masumi Mitsui 10th Bn

NMM 2010.23.2.4.551 10th Battalion

NMM 2016.21.1.2.3 Stanley Park Vimy Memorial

NMM 2001.4.4.5.40 Group Holding Wreaths at Memorial

CVA99-925MD Young Boy at Memorial]

Finding Voice

Japanese Canadians speak up for the right to be recognized as full citizens.

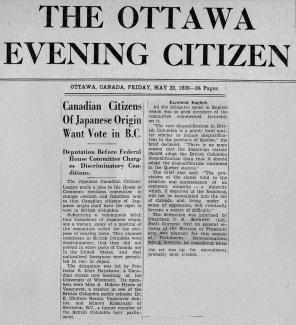

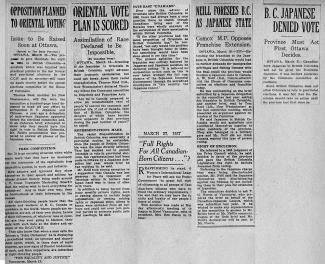

Japanese Canadians speak up demanding equal rights to white Canadians as early as 1900. Community leaders like Tomekichi Homma formally object to injustice: Homma challenges the law denying Japanese Canadians the right to vote, and the Supreme Court of Canada rules in his favour, but the Privy Council in London later overrules that decision. Still, Japanese Canadians believe they deserve the same rights as white British subjects.

Transcript

[Atmospheric piano music]

[A black and white split-image: a group of young boys and girls pose on the left, while on the right, three men and a woman stand on the steps leading to a parliament building. Then, in the photograph featuring the youngsters, a girl sitting in the front row, wearing shorts and smiling an impish grin, is highlighted. Next, a silver-haired woman sits in a chair, wearing a red and black scarf emblazoned with a striking First Nations pattern.

>> A woman’s voice:

The province was totally against having Asian-Canadians, Asian immigrants becoming Canadians.

[An archival photograph appears of a Japanese family. The mother stands with her young daughter to the left, while the father, holding his infant son in his lap, sits to the right.]

I was a child, but you have to remember that people like my parents, they were the ones who were dealing with these things and, they…many of them were activists in the sense that they were protecting each other.

>> The woman speaks:

This was the period when the Nisei, the second generation started to speak out.

[The same family, a few years later with the addition of another boy and girl, appears in another archival photograph]

>> The woman speaks:

Many of them were already university-educated, but still they were not able to get the right to vote which meant that they could not get professional jobs. A Japanese Canadian Citizens League, a league was formed, by the Nisei, through which they decided to try to get the right to vote.

[A black and white photograph: a group of adults - mostly men, along with a few women - stand in front of a building called:“1928: Japanese Hall”. Handwritten on the photograph are the words: ”JCCL First Annual Convention, 1936.” Next, three men stand with a woman on the steps of a Parliament building.]

>> Woman’s voice:

So, they were all people who were well-educated.

>> The woman speaks:

And when they went to Ottawa, to ask for the right to vote, interestingly, the committee that met with them…they were shocked that these 4 young people spoke English so well.

[Once again, the four young people stand in front of the Parliament building.]

Even though they were impressed with them, they ended up that it was up to the province to decide whether they could get the right to vote.

>>The woman appears:

And provincially, the provincial government was not willing to give that to any Asian-Canadian, Asians born in Canada or immigrants.

[The girl with the impish smile, now a pre-teenager with curly, shoulder-length hair, stands in an internment settlement.]

But - we do have a voice, and I think it’s very important that we use that voice.

>> The woman reappears:

If something is unjust, I think you should speak, and if you do speak and you’re called a troublemaker – so what?

[The woman sits in an old building with wood slats.]

[Onscreen text: Archival photographs courtesy of Grace Eiko Thomson Family Archive

JCCC 2001-11-091 Japanese Canadian Citizens League

NNM 2000.14.1.1.1 JCCL Delegation in Ottawa, 1936]